- Home

- Terry McDermott

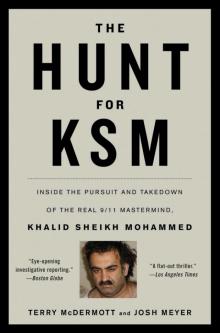

The Hunt for KSM Page 6

The Hunt for KSM Read online

Page 6

CHAPTER 3

Jihad

New York City, 1992

In early September of 1992, a pair of men traveling with fake passports arrived from Peshawar, Pakistan, at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport and presented themselves at immigration control. One of the men, Ahmad Mohammed Ajaj, carried a crudely forged Swedish passport with his picture pasted in it. The document was instantly recognized as fraudulent. A subsequent search of Ajaj’s checked baggage revealed diagrams and chemical recipes for making bombs. He was arrested on the spot. The other man was Abdul Basit Abdul Karim, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s nephew. He had a valid Iraqi passport in the name of Ramzi Ahmed Yousef, but the passport did not contain a visa for the United States. He had no checked luggage, just a carry-on bag. He had stowed most of his materials, including the bomb recipes, in Ajaj’s bag. Questioned about the lack of a visa, he immediately admitted the passport was not his, gave his real name, and requested political asylum. The immigration holding facility was full, so he was assigned a court date and released on his own recognizance. He took a taxi to New Jersey, went to a mosque, and soon recruited a makeshift crew to assist him in blowing up the World Trade Center.1

Basit and Mohammed had separated when, after high school, Mohammed went to Chowan, in North Carolina, and Basit to the technical college in Wales a few years later. They reunited briefly in Peshawar, when Basit, on a break from school, visited in 1988, and again when he returned in 1991. By then the Soviet war had ended but the mujahideen training camps remained, churning out fresh batches of would-be warriors. Basit became so adept at making bombs at Khalden that trainees called him the Chemist.

Basit didn’t waste time on debates about the future of jihad and where it should be waged; he began making plans and finding men to carry them out. His first recruit was the hapless Ajaj, a Palestinian who had immigrated to the United States in 1991 and worked at menial restaurant jobs before leaving to take jihad training in Afghanistan—without thinking to renew his visa. After his training, he was stranded in Pakistan. When Basit offered him a first-class return ticket to the U.S. in exchange for carrying his bags, he accepted. Basit also gave Ajaj the bad passport that led to his arrest, while he kept the valid Iraqi passport, purchased at a Peshawar bazaar for a mere $100, for himself.

Basit was equally persuasive with others, including Pakistani cousins who credited him with guiding them on a path to jihad. Months prior to his arrival in the United States, Basit had renewed acquaintances with a childhood friend from Kuwait, Abdul Hakim Murad. Murad at the time was in the United States, struggling to get licensed as a commercial pilot. He went to five different flight schools before eventually earning his license.2

When Basit contacted Murad, he told him he had taken up the cause of jihad and wanted to attack Israel. This would come as no surprise to anyone who knew him. Basit used to profess his devotion to the Palestinian cause by declaring himself Pakistani by birth, Palestinian by choice. Israel was a tough target, however; it was alert to danger and its defenses were formidable. Basit said he would attack Jews in the United States instead. He knew from Mohammed’s college experience and Murad’s travels around the country for flight training that access to the United States was generally simple and that, once there, the freedom of movement was nearly absolute. He asked Murad if he could suggest any Jewish targets. Murad shared Basit’s low opinion of Israel. “If you ask anybody, even if you ask children, they will tell you that the U.S. is supporting Israel, and Israel is killing our Muslim brothers in Palestine,” he said.

Murad agreed to think about potential targets and, while Basit scouted Brooklyn for Jews, gave it some thought. Eventually, Murad told Basit that the World Trade Center would make an inviting target. New York had a lot of Jews, he knew, and the Twin Towers were bound to be a workplace for many of them.

Throughout his time in New York that fall and winter, Basit stayed in touch with his uncle Mohammed. They talked often by telephone. Some of their conversation was social, some of it related to Basit’s project, for which he was strapped for cash. The bomb he wanted to build didn’t need to be hugely expensive, but it nonetheless took money to buy the materials and to live in the meantime. Mohammed was impressed with how easily Basit seemed able to operate in the United States. He pitched in, wiring $660 to the bank account of one of Basit’s accomplices.

Basit finally settled on Murad’s suggestion. He had several different ideas on what sort of bomb he could build. He toyed with the idea of building a device that contained cyanide, the idea being that the release of the deadly gas into the Trade Center’s ventilation system would neatly kill all its occupants. This design proved too daunting and expensive, so he settled on the cheapest sort of bomb he knew how to build—an ordinary fertilizer bomb made with urea nitrate. He built several small prototypes and drove out to the New Jersey countryside to blow them up. “Making chocolate” was how he described the process to Murad.

The eventual attack was a ramshackle, almost cartoonish affair. Basit designed and built a bomb that in the end cost only $3,000. The first time they tried to put the bomb in place in the parking garage, his crew crashed their vehicle en route and had to delay the attack. On February 26, the day of the actual attack, Basit overslept by several hours and his accomplices let him slumber on. Though hours late, the bomb was successfully stowed, although inefficiently arranged, behind shipping crates in a rental van and parked in the basement of the North Tower. After setting the timer, Basit had only seven minutes to get himself and his helpers out of the building. He jumped from the van to a getaway car, which then got trapped behind a cargo truck for several agonizing minutes in the basement. They made it out with mere moments to spare.

Basit intended the bomb to topple the North Tower into the South Tower, somehow bringing them both to the ground. When the bomb exploded, the damage was much less significant. Still, it fractured several structural columns and shook the giant tower.

Basit fled the country that same night on a first-class flight to Pakistan from JFK, leaving his ragtag crew to suffer the consequences. On his way out of town he mailed letters to news organizations claiming responsibility for the attack:

We are, the fifth battalion in the LIBERATION ARMY, declare our responsibility for the explosion on the mentioned building. This action was done in response for the American political, economical, and military support to Israel the state of terrorism and to the rest of the dictator countries in the region.

Basit went on to detail a litany of complaints about the evils America had done in the Middle East and elsewhere, and signed the letter in the names of Al-Farrek Al-Rokn and Abu Bakr Al-Makee. There was no Al-Farrek or Abu Bakr. There was no Liberation Army, either—just Basit and Mohammed and their fervid imaginations. The World Trade Center was just the beginning. With the Trade Center bomb, Basit and Mohammed had come upon a new, off-center notion of jihad: not just a war against states, but a nonstop, all-out war on all enemies, anywhere they could be reached.

Federal Plaza, New York City, 1993

Basit’s truck bomb provided the first glimmerings of a new realization for the few Americans who thought about such things—international terrorism was a nearly unknowable threat. It could spring from the ground almost anywhere and, contrary to most expectations, it did not have to be sponsored by pariah states.

This should not have come as a great surprise. The United States had significant experience with terrorism over the prior two decades. Almost all of it came from domestic sources—the Weathermen, Black Panthers, and scores of other, less-well-known groups. There had been hundreds of bombings across the nation, very few of them sponsored by opposing states. Nothing that had occurred approached the ambition of the Trade Center attack, but several of the explosions had caused significant injury, death, and expense.

At first, investigators were not even certain that the Trade Center had been bombed. Initial reports suggested some organic cause, perhaps an electrical transformer explosion

. Federal officials did not immediately respond, leaving the first investigations to local authorities. An FBI agent who happened to be in the neighborhood having lunch when the bomb went off ambled over to the site, took one look, and ambled back to the office.3 Within the first hours, however, clear evidence of a bomb was uncovered and federal agents descended on the basement.

The New York City field office of the FBI had long been the largest and most headstrong of the bureaus spread across the country. It had to be. Virtually every kind of crime the Bureau dealt with occurred within its jurisdiction. Its leaders had always felt that no one understood what they faced as well as they did. As a result, the office had every peculiarity of every other office plus some of its own invention.

Organizationally, it was within the federal judicial district known as the Southern District of New York. This was sometimes referred to—mockingly, but enviously, too—as the Sovereign District of New York. It was in many ways a separate fiefdom from the rest of the Bureau, creating its own rules and procedures. The agent in charge of the office, unlike all but one other agent in charge, held the rank of an assistant director of the entire FBI.

If the New York office’s relationship with the rest of the Bureau was rocky, its relationship with its New York neighbor—the New York City police department—was worse. The Bureau had been an insular organization from its start under J. Edgar Hoover, famed for doing things its own way and its own way only. The NYPD equaled or surpassed it in hubris, dwarfed it in size, and was equally blind to its own flaws. The two agencies argued about almost everything—who would get what cases, where they would be tried, who would interview which witnesses. At times, unable to reach any compromise whatsoever, they interviewed witnesses twice, neither side willing to either give up the right to do so or to trust the work of the other.

In an attempt to bridge some of these gaps, the two organizations had in the 1970s teamed together and built a task force to investigate bank robberies, which were often federal crimes. This prepared the ground for the formation in 1980 of a Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) staffed with a dozen FBI agents, most of who came from its M-9 special bomb squad, and a dozen NYPD detectives. It would later grow to include hundreds of people drawn from the FBI, NYPD, DEA, the Port Authority, fire departments, and scores of other agencies—especially after 9/11.

Before the 1993 Trade Center attack, there was no template—nor, it seemed, was there any need—for fighting international terrorism, and the JTTF worked mainly on domestic terrorism. What little foreign intelligence work was being done focused on Sudanese and Egyptian diplomats at the United Nations, not international terrorists. (The Bureau’s first investigative work on Osama bin Laden would occur because bin Laden was then living in Sudan and the Bureau had previously done the investigative work that led to the deportation of a Sudanese diplomat.) This was not glamorous work, nor was it particularly well rewarded.

The FBI historically was an organization driven by data. Its meticulously maintained archives of fingerprints and case files were among the largest and most useful criminal databases in the world. Internally, statistics drove the FBI’s bureaucracy. You got promoted by accruing numbers—interviews, arrests, convictions. By its own metrics, this was a strict meritocracy. But to view it that way would be to ignore those superior agents who, for whatever reason, seldom made arrests.

Counterterrorism was in a uniquely bad position within this system. Until something horrible happened, no one paid it much attention. Agents could get stuck there. If you were lucky, you’d rack up an arrest every couple of years and a conviction every decade. It wasn’t the place you wanted to be in the Bureau unless you really cared about what you were doing. The real action was in chasing mobsters and white-collar criminals, slapping the cuffs on them and perp-walking them into the courthouse.

CT agents were pitied—or, worse, scorned—within the Bureau. Some thought you got stuck doing terrorism cases only if you were lazy or incompetent. The degree to which terrorism was a bureaucratic backwater was made obvious in a meeting not long after the World Trade Center bomb exploded. Federal prosecutors, New York police, U.S. Treasury agents, the FBI, and the CIA gathered to share information. After preliminary discussions were completed, one of the CIA men in attendance (none of whom would reveal their names) addressed the lead prosecutors and in all sincerity asked: How do we stop international terrorism?

The FBI guys were dumbfounded. Isn’t that your job? they asked.

As it turned out, no. The CIA was in the international intrigue, information, and great power struggle businesses. Its knowledge of and methods for counteracting Islamist terror were virtually nonexistent. The FBI did not have much more institutional knowledge. What it did have in the Trade Center bombing, however, was a crime—a federal crime—and it was the Bureau’s responsibility to investigate it.

The big break in the Trade Center investigation occurred within hours of the attack. Investigators, laboriously sifting through the debris in the North Tower basement, found a piece of the wreckage of the Ford Econoline van that Basit had used to transport the bomb. An alert cop examined it for a VIN number and found one. From there it was a simple matter of running the number through motor vehicle databases, which revealed that the van was a Ryder rental vehicle. Investigators then found the agency that had rented the van, and the name of the person to whom it had been rented. They caught another break when the renter, a man named Mohammed Salameh, called the rental agency to report the van stolen and ask for his $400 security deposit back. Because Basit was the financier and had fled the country, leaving his accomplices on their own, Salameh was broke and desperately needed the cash from the deposit. When he showed up to collect his money, he was greeted by an undercover FBI agent pretending to be a Ryder manager. Refund in hand, Salameh was arrested on his way out. Once investigators had him in custody, the others involved in the conspiracy were quickly identified. The lone exception was Basit, whom the others knew only as Rashid.

Seven men were implicated in the attack. Each was assigned his own team of investigators. Frank Pellegrino’s team got Rashid.

Pellegrino was a young FBI agent from Long Island. He’d been a certified public accountant at Coopers & Lybrand before deciding to give up the security—and boredom—of that career in 1987. “If I had to add up another book of numbers I was gonna shoot myself,” he told friends. He had gotten his start in accounting because his junior varsity baseball coach taught the subject at Elmont Memorial High School in Nassau County and he thought he’d get an easy ride. His Irish mother had been a detective from a long line of Irish cops and so he applied at the Bureau. He waited more than a year for a response, and was thinking he’d stay in accounting, when the call finally came.

Pellegrino was ambitious. Once he joined the FBI he almost immediately began taking night classes back at St. John’s University in Queens, where he’d gotten his accounting degree. In a remarkably quick four years, he had earned a law degree while working long days at the FBI. The Bureau was full of accountants and had a fair sprinkling of lawyers. Few, if any, agents were both, though anyone in the field office would tell you that Pellegrino didn’t look or act at all like an accountant or a lawyer—or an FBI agent, for that matter.

Pellegrino’s early experience at the Bureau was typical for the time. Like others in the Southern District, he spent the first years of his career on drug cases. He was then moved to the counterterrorism squad, which largely entailed surveilling people going in and out of mosques. When Neil Herman, head of the JTTF, gave Pellegrino his Trade Center assignment, it was at best inauspicious; “Rashid” seemed like a sideshow to the main event. Nonetheless, Pellegrino and two other men from the JTTF, Treasury agent Tom Kelly and Brian Parr from the Secret Service, tracked leads all over Brooklyn and Queens. Others among the WTC attack team seemed more important. Several had connections to a radical preacher, Omar Abdel-Rahman, known as the Blind Sheikh. It was to one of the Blind Sheikh’s mosques that Basit had gone

when he first arrived in the United States. But as the other suspects were gradually rounded up, they all talked about the mysterious Rashid, who flew in and out of their lives in a virtual heartbeat, apparently bearing the World Trade Center plan with him. He had more wherewithal and savvy than the others. He seemed to have connections overseas. When investigators learned that Rashid had flown out of the country the night of the attack, he took on even more importance.

Investigating the bombing remained a slow process. Information was scant. Pellegrino’s team eventually tracked back through the immigration system and found Basit’s real name and where he was from. Bit by bit, they began to assemble a profile, and all signs pointed east—to Pakistan.

Islamabad, Pakistan, 1993

An international manhunt was launched for Basit, with a reward of $2 million for his capture. Tens of thousands of matchbooks were printed up with his photo emblazoned on them. The matchbooks were air-dropped over half of Pakistan. Basit—or, in reality, his alter ego, Ramzi Yousef—became a kind of celebrity in the jihadi world. Every time a bomb went off anywhere, his name came up. And when his name came up, one or more of the team of Pellegrino, Parr, and Kelly hit the road.

It got to be kind of a joke. Because Basit had officially become public enemy number one, he was spotted everywhere. He was driving a gasoline-filled truck in Bangkok. He was bombing American embassies in Asia. Nothing came of the early leads and rumors, so the agents were left to scour every bit of evidence they had on Basit’s crew. They tried to trace the money behind the attack, but it had required so little that even that task proved daunting. They did find a record of a bank transfer into the local account of one of Basit’s comrades—Salameh—that they couldn’t figure out. It was for $660 from someone identified on the wire transfer record as Khalid Shaykh from Doha.

The Hunt for KSM

The Hunt for KSM